Earlier this month I had the pleasure of giving a talk entitled ‘It’s good to talk – especially in lectures!’ at Moray House, School of Education. The presentation focused on my research into the interactions that take place during active learning lectures in physics.

To my surprise both the approaches that I’ve used and the findings uncovered have generated interest and discussions across the disciplines, from education to biology and everything in between. So to keep the conversation going, here is a short summary of the talk and the discussion that followed it. Thoughts welcome!

Introduction

For many undergraduate students, lectures are the primary method of instruction, yet they remain very much like a black box; we put students in and expect them to come out having gained something, but very little research has looked in detail at what actually takes place during them, and how (or whether) that leads to learning.

What we do know is that research shows that ‘reformed’, active learning approaches lead to better learning outcomes than traditional lectures. But if we are to do this effectively we need more detail about what activities take place, about what works and what doesn’t in different contexts and how different combinations of activities work together.

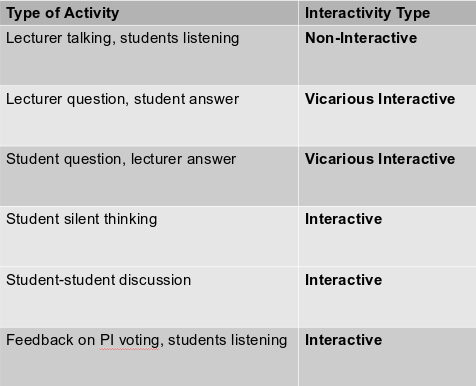

In Physics Education Research the term ‘Interactive Engagement’ is used synonymously with ‘active learning’. This points to the key difference between active and traditional lectures: the quantity and quality of interactions that students experience. This interactivity may be students interacting with the material, discussing with each other, or engaging in dialogue with the lecturer. My research, and my talk discussed these interactions from three perspectives: 1) A quantitative analysis 2) a qualitative analysis of lecturer-student interactions and 3) an analysis of peer-discussions.

All my research involves first year physics lectures taught by Ross Galloway. He uses a ‘flipped’ approach in which students do pre-readings and a quiz before the lecture, while an active learning component is introduced into the lectures through the use of clickers and Peer Instruction (link includes a two minute video introduction).

- Quantitative Analysis

The first piece of work I discussed (1) aimed to answer the questions ‘What types of interaction take place?’, and ‘How much time is spent on these interactions during lectures?’

For this work I developed the Framework for Interactive Learning in Lectures (FILL) – a simple coding system, which we hope others will use to characterise their lectures, enabling a comparison across different subject areas and contexts.

The most surprising result (given the distinct active learning approach) is that 55% of the lecture, on average, was spent on the lecturer talking. It is important to note however, that this is very different from the monologue experienced in traditional lectures, which is often primarily about content delivery. Instead these episodes of talk are targeted explanations which often happen in response to or in preparation for an active learning component.

- Lecturer-Student Interactions

This work explored lecturer-student dialogues in more detail using a qualitative approach (2). My questions were: ‘What are the roles that dialogues have in lectures?’ and ‘How do they support learning?’

One aspect that became clear was the challenge of creating dialogue in such large classes (200+ students). Even if one student answers (or asks) a question, the remaining 199 students are not taking an active part in the exchange. But I also realised that this can partly be overcome by the use of electronic voting systems. The sequence of 1) the lecture asking a clicker question 2) students responding by voting and 3) the lecture providing feedback/responding to the vote, can be thought of as a dialogue that is mediated by the clicker technology.

In fact this three part exchange follows the IRF (Initiation Response Feedback) form first described by Sinclair and Coulthard (3) and commonly observed in educational settings. Indeed my analysis of the verbal interactions in the lectures showed that most dialogues were in the IRF form.

However, IRF has been criticised for being teacher centred and typically associated with closed questions and factual recall. Despite this, during my analysis of the lectures I felt that the overall experience was interactive, student centred and dialogic, certainly compared to traditional lectures.

Other researchers have noted similar findings in the school setting, and have captured this through the notion of ‘ideologically dialogic’ (4), which describes a learning environment that encourages the student voice and is student centred, even though the structure of the individual dialogues is monologic or authoritative.

- Peer-Interactions

Finally I explored student dialogues that take place during Peer Instruction (5) in order to try and understand how they lead to learning. We know that more students select the correct answer to the clicker question after they have had a chance to discuss it with others, implying that something important happens during that discussion.

Student dialogues were recorded using smart pens. By analysing the dialogues I found a number of occasions where there appears to be a ‘light bulb’ moment for a student. Sometimes these happened after a student had mentioned an individual piece of information (knowledge element), sometimes after they had made a link to a related idea (such as the student who referred to an episode of the Big Bang Theory), and sometimes when a student suggested (often implicitly) a different problem solving approach.

Discussion

After the talk there was a wide-ranging discussion covering issues such as gender (does gender affect how students experience interactions, do they approach interactions in the lecture and outside the lecture theatre differently?) and the use of lecture capture. If talk is to be encouraged in lectures, does lecture capture stifle talk, and if so how can we best balance this? What are the ethical considerations of lecture capture that includes students’ voices? and does the increased use of interactions in lectures change the value of lecture capture, as a tool for students’ learning?

Acknowledgements

All of this research took place in collaboration with the Edinburgh Physics Education Research Group. Particular thanks go to Ross Galloway for giving me access to his students and to his lectures – I imagine that was a daunting experience but I know he has also said it was enlightening and would encourage others to watch the lecture capture videos of their teaching – perhaps using our framework for interactive learning in lectures as a guide.

About the author

Anna Wood has a degree and a PhD in physics and an MSc in E-learning. It was during this course that she discovered a fascination for how people learn, and she now combines physics with education research, collaborating informally with the physics education research group at Edinburgh. She can be contacted on annakwood@physics.org

References:

- Wood et al. ‘Characterizing interactive engagement activities in a flipped introductory physics class’ Phys. Rev. Phys.Educ. Res. 12, 010140 (2016)

- Wood et al. ‘Teacher-Student Discourse in Active Learning Lectures: A Case Study from Undergraduate Physics’ Submitted

- Sinclair, J. & Coulthard, M. (1975)

- O’Connor, C., & Michaels, S. (2007). When Is Dialogue “Dialogic”? Human Development, 50(5), 275–285.